PySpark Performance Tuning and Optimization

PySpark pipelines that work beautifully with test data often crawl (or crash) in production. For example, a pipeline runs great at a small scale, with maybe a few hundred records finishing in under a minute. Then the company grows, and that same pipeline now processes hundreds of thousands of records and takes 45 minutes. Sometimes it doesn't finish at all. Your team lead asks, "Can you make this faster?"

In this tutorial, we’ll see how to systematically diagnose and fix those performance problems. We'll start with a deliberately unoptimized pipeline (47 seconds for just 75 records — yikes!), identify exactly what's slow using Spark's built-in tools, then fix it step-by-step until it runs in under 5 seconds. Same data, same hardware, just better code.

Before we start our optimization, let's set the stage. We've updated the ETL pipeline from the previous tutorial to use production-standard patterns, which means we're running everything in Docker with Spark's native parquet writers, just like you would in a real cluster environment. If you aren’t familiar with the previous tutorial, don’t worry! You can seamlessly jump into this one to learn pipeline optimization.

Getting the Starter Files

Let's get the starter files from our repository.

# Clone the full tutorials repo and navigate to this project

git clone <https://github.com/dataquestio/tutorials.git>

cd tutorials/pyspark-optimization-tutorialThis tutorial uses a local docker-compose.yml that exposes port 4040 for the Spark UI, so make sure you cloned the full repo, not just the subdirectory.

The starter files include:

- Baseline ETL pipeline code (in

src/etl_pipeline.pyandmain.py) - Sample grocery order data (in

data/raw/) - Docker configuration for running Spark locally

- Solution files for reference (in

solution/)

Quick note: Spark 4.x enables Adaptive Query Execution (AQE) by default, which automatically handles some optimizations like dynamic partition coalescing. We've disabled it for this tutorial so you can see the raw performance problems clearly. Understanding these issues helps you write better code even when AQE is handling them automatically, which you'll re-enable in production.

Now, let's run this production-ready baseline to see what we’re dealing with.

Running the baseline

Make sure you're in the correct directory and start your Docker container with port access:

cd /tutorials/pyspark-optimization-tutorial

docker compose run --rm --service-ports labThis opens an interactive shell inside the container. The --service-ports flag exposes port 4040, which you'll need to access Spark's web interface. We'll use that in a moment to see exactly what your pipeline is doing.

Inside the container, run:

python main.pyPipeline completed in 47.15 seconds

WARNING: Total allocation exceeds 95.00% of heap memory

[...25 more memory warnings...]47 seconds for 75 records. Look at those memory warnings! Spark is struggling because we're creating way too many partition files. We're scanning the data multiple times for simple counts. We're doing expensive aggregations without any caching. Every operation triggers a full pass through the data.

The good news? These are common, fixable mistakes. We'll systematically identify and eliminate them until this runs in under 5 seconds. Let's start by diagnosing exactly what's slow.

Understanding What's Slow: The Spark UI

We can't fix performance problems by guessing. The first rule of optimization: measure, then fix.

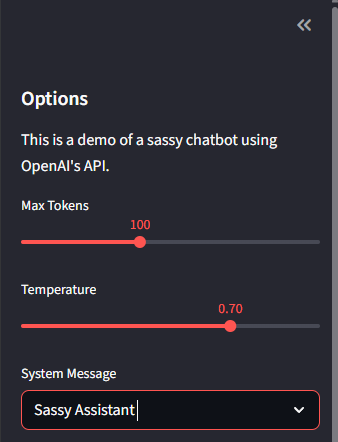

Spark gives us a built-in diagnostic tool that shows exactly what our pipeline is doing. It's called the Spark UI, and it runs every time you execute a Spark job. For this tutorial, we've added a pause at the end of our main.py job so you can explore the Spark UI. In production, you'd use Spark's history server to review completed jobs, but for learning, this pause lets you click around and build familiarity with the interface.

Accessing the Spark UI

Remember that port 4040 we exposed with our Docker command? Now we're going to use it. While your pipeline is running (or paused at the end), open a browser and go to http://localhost:4040.

You'll see Spark's web interface showing every job, stage, and task your pipeline executed. This is where you diagnose bottlenecks.

What to Look For

The Spark UI has a lot of tabs and metrics, which can feel overwhelming. For our work today we’ll focus on three things:

The Jobs tab shows every action that triggered execution. Each .count() or .write() creates a job. If you see 20+ jobs for a simple pipeline, you're doing too much work.

Stage durations tell you where time is being spent. Click into a job to see its stages. Spending 30 seconds on a count operation for 75 records? That's a bottleneck.

Number of tasks reveals partitioning problems. See 200 tasks to process 75 records? That's way too much overhead.

Reading the Baseline Pipeline

Open the Jobs tab. You'll see a table that looks messier than you'd expect:

Job Id Description Duration

0 count at NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:0 0.5 s

1 count at NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:0 0.1 s

2 count at NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:0 0.1 s

...

13 parquet at NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:0 3 s

15 parquet at NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:0 2 s

19 collect at etl_pipeline.py:195 0.3 s

20 collect at etl_pipeline.py:201 0.3 sThe descriptions aren't particularly helpful, but count them. 22 jobs total. That's a lot of work for 75 records!

Most of these are count operations. Every time we logged a count in our code, Spark had to scan the entire dataset. Jobs 0-12 are all those .count() calls scattered through extraction and transformation. That's inefficiency #1.

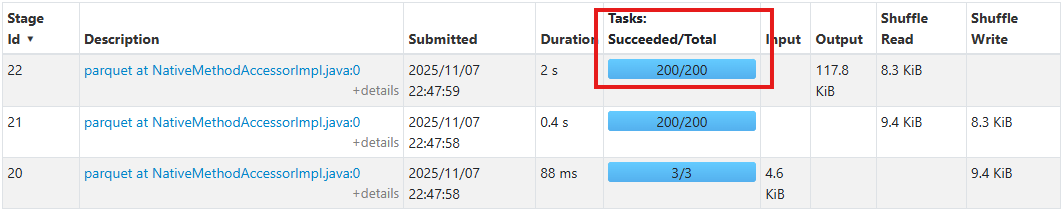

Jobs 13 and 15 are our parquet writes. If you click into job 13, you'll see it created around 200 tasks to write 75 records. That's why we got all those memory warnings: too many tiny files means too much overhead.

Jobs 19 and 20 are the collect operations from our summary report (you can see the line numbers: etl_pipeline.py:195 and :201). Each one triggers more computation.

The Spark UI isn't always pretty, but it's showing us exactly what's wrong:

- 22 jobs for a simple pipeline - way too much work

- Most jobs are counts - rescanning data repeatedly

- 200 tasks to write 75 records - partitioning gone wrong

- Separate collection operations - no reuse of computed data

You don't need to understand every Java stack trace; you just need to count the jobs, spot the repeated operations, and identify where time is being spent. That's enough to know what to fix.

Eliminating Redundant Operations

Look back at those 22 jobs in the Spark UI. Most of them are counts. Every time we wrote df.count() to log how many records we had, Spark scanned the entire dataset. Right now, that's just 75 records, but scale to 75 million, and those scans eat hours of runtime.

Spark is lazy by design, so transformations like .filter() and .withColumn() build a plan but don't actually do anything. Only actions like .count(), .collect(), and .write() trigger execution. Usually, this is good because Spark can optimize the whole plan at once, but when you sprinkle counts everywhere "just to see what's happening," you're forcing Spark to execute repeatedly.

The Problem: Logging Everything

Open src/etl_pipeline.py and look at the extract_sales_data function:

def extract_sales_data(spark, input_path):

"""Read CSV files with explicit schema"""

logger.info(f"Reading sales data from {input_path}")

# ... schema definition ...

df = spark.read.csv(input_path, header=True, schema=schema)

# PROBLEM: This forces a full scan just to log the count

logger.info(f"Loaded {df.count()} records from {input_path}")

return dfThat count seems harmless because we want to know how many records we loaded, right? But we're calling this function three times (once per CSV file), so that's three full scans before we've done any actual work.

Now look at extract_all_data:

def extract_all_data(spark):

"""Combine data from multiple sources"""

online_orders = extract_sales_data(spark, "data/raw/online_orders.csv")

store_orders = extract_sales_data(spark, "data/raw/store_orders.csv")

mobile_orders = extract_sales_data(spark, "data/raw/mobile_orders.csv")

all_orders = online_orders.unionByName(store_orders).unionByName(mobile_orders)

# PROBLEM: Another full scan right after combining

logger.info(f"Combined dataset has {all_orders.count()} orders")

return all_ordersWe just scanned three times to count individual files, then scanned again to count the combined result. That's four scans before we've even started transforming data.

The Fix: Count Only What Matters

Only count when you need the number for business logic, not for logging convenience.

Remove the counts from extract_sales_data:

def extract_sales_data(spark, input_path):

"""Read CSV files with explicit schema"""

logger.info(f"Reading sales data from {input_path}")

schema = StructType([

StructField("order_id", StringType(), True),

StructField("customer_id", StringType(), True),

StructField("product_name", StringType(), True),

StructField("price", StringType(), True),

StructField("quantity", StringType(), True),

StructField("order_date", StringType(), True),

StructField("region", StringType(), True)

])

df = spark.read.csv(input_path, header=True, schema=schema)

# No count here - just return the DataFrame

return dfRemove the count from extract_all_data:

def extract_all_data(spark):

"""Combine data from multiple sources"""

online_orders = extract_sales_data(spark, "data/raw/online_orders.csv")

store_orders = extract_sales_data(spark, "data/raw/store_orders.csv")

mobile_orders = extract_sales_data(spark, "data/raw/mobile_orders.csv")

all_orders = online_orders.unionByName(store_orders).unionByName(mobile_orders)

logger.info("Combined data from all sources")

return all_ordersFixing the Transform Phase

Now look at remove_test_data and handle_duplicates. Both calculate how many records they removed:

def remove_test_data(df):

"""Filter out test records"""

df_filtered = df.filter(

~(upper(col("customer_id")).contains("TEST") |

upper(col("product_name")).contains("TEST") |

col("customer_id").isNull() |

col("order_id").isNull())

)

# PROBLEM: Two counts just to log the difference

removed_count = df.count() - df_filtered.count()

logger.info(f"Removed {removed_count} test/invalid orders")

return df_filteredThat's two full scans (one for df.count(), one for df_filtered.count()) just to log a number. Here's the fix:

def remove_test_data(df):

"""Filter out test records"""

df_filtered = df.filter(

~(upper(col("customer_id")).contains("TEST") |

upper(col("product_name")).contains("TEST") |

col("customer_id").isNull() |

col("order_id").isNull())

)

logger.info("Removed test and invalid orders")

return df_filteredDo the same for handle_duplicates:

def handle_duplicates(df):

"""Remove duplicate orders"""

df_deduped = df.dropDuplicates(["order_id"])

logger.info("Removed duplicate orders")

return df_dedupedCounts make sense during development when we're validating logic. Feel free to add them liberally - check that your test filter actually removed 10 records, verify deduplication worked. But once the pipeline works? Remove them before deploying to production, where you'd use Spark's accumulators or monitoring systems instead.

Keeping One Strategic Count

Let's keep exactly one count operation in main.py after the full transformation completes. This tells us the final record count without triggering excessive scans during processing:

def main():

# ... existing code ...

try:

spark = create_spark_session()

logger.info("Spark session created")

# Extract

raw_df = extract_all_data(spark)

logger.info("Extracted raw data from all sources")

# Transform

clean_df = transform_orders(raw_df)

logger.info(f"Transformation complete: {clean_df.count()} clean records")

# ... rest of pipeline ...One count at a key checkpoint. That's it.

What About the Summary Report?

Look at what create_summary_report is doing:

total_orders = df.count()

unique_customers = df.select("customer_id").distinct().count()

unique_products = df.select("product_name").distinct().count()

total_revenue = df.agg(sum("total_amount")).collect()[0][0]

# ... more separate operations ...Each line scans the data independently - six separate scans for six metrics. We'll fix this properly in a later section when we talk about efficient aggregations, but for now, let's just remove the call to create_summary_report from main.py entirely. Comment it out:

load_to_parquet(clean_df, output_path)

load_to_parquet(metrics_df, metrics_path)

# summary = create_summary_report(clean_df) # Temporarily disabled

runtime = (datetime.now() - start_time).total_seconds()

logger.info(f"Pipeline completed in {runtime:.2f} seconds")Test the Changes

Run your optimized pipeline:

python main.pyWatch the output. You'll see far fewer log messages because we're not counting everything. More importantly, check the completion time:

Pipeline completed in 42.70 secondsWe just shaved off 5 seconds by removing unnecessary counts.

Not a massive win, but we're just getting started. More importantly, check the Spark UI (http://localhost:4040) and you should see fewer jobs now, maybe 12-15 instead of 22.

Not all optimizations give massive speedups, but fixing them systematically adds up. We removed unnecessary work, which is always good practice. Now let's tackle the real problem: partitioning.

Fixing Partitioning: Right-Sizing Your Data

When Spark processes data, it splits it into chunks called partitions. Each partition gets processed independently, potentially on different machines or CPU cores. This is how Spark achieves parallelism. But Spark doesn't automatically know the perfect number of partitions for your data.

By default, Spark often creates 200 partitions for operations like shuffles and writes. That's a reasonable default if you're processing hundreds of gigabytes across a 50-node cluster, but we're processing 75 records on a single machine. Creating 200 partition files means:

- 200 tiny files written to disk

- 200 file handles opened simultaneously

- Memory overhead for managing 200 separate write operations

- More time spent on coordination than actual work

It's like hiring 200 people to move 75 boxes. Most of them stand around waiting while a few do all the work, and you waste money coordinating everyone.

Seeing the Problem

Open the Spark UI and look at the Stages tab. Find one of the parquet write stages (you'll see them labeled parquet at NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:0).

Look at the Tasks: Succeeded/Total column and you'll see 200/200. Spark created 200 separate tasks to write 75 records. Now, look at the Shuffle Write column, which is probably showing single-digit kilobytes. We're using massive parallelism for tiny amounts of data.

Each of those 200 tasks creates overhead: opening a file handle, coordinating with the driver, writing a few bytes, then closing. Most tasks spend more time on coordination than actual work.

The Fix: Coalesce

We need to reduce the number of partitions before writing. Spark gives us two options: repartition() and coalesce().

Repartition does a full shuffle - redistributes all data across the cluster. It's expensive but gives you exact control.

Coalesce is smarter. It combines existing partitions without shuffling. If you have 200 partitions and coalesce to 2, Spark just merges them in place, which is much faster.

For our data size, we want 1 partition - one file per output, clean and simple.

Update load_to_parquet in src/etl_pipeline.py:

def load_to_parquet(df, output_path):

"""Save to parquet with proper partitioning"""

logger.info(f"Writing data to {output_path}")

# Coalesce to 1 partition before writing

# This creates a single output file instead of 200 tiny ones

df.coalesce(1) \

.write \

.mode("overwrite") \

.parquet(output_path)

logger.info(f"Successfully wrote data to {output_path}")When to Use Different Partition Counts

You don’t always want one partition. Here's when to use different counts:

For small datasets (under 1GB): Use 1-4 partitions. Minimize overhead.

For medium datasets (1-10GB): Use 10-50 partitions. Balance parallelism and overhead.

For large datasets (100GB+): Use 100-500 partitions. Maximize parallelism.

General guideline: Aim for 128MB to 1GB per partition. That's the sweet spot where each task has enough work to justify the overhead but not so much that it runs out of memory.

For our 75 records, 1 partition works perfectly. In production environments, AQE typically handles this partition sizing automatically, but understanding these principles helps you write better code even when AQE is doing the heavy lifting.

Test the Fix

Run the pipeline again:

python main.pyThose memory warnings should be gone. Check the timing:

Pipeline completed in 20.87 secondsWe just saved another 22 seconds by fixing partitioning. That's cutting our runtime in half. From 47 seconds in the original baseline to 20 seconds now, and we've only made two changes.

Check the Spark UI Stages tab. Now your parquet write stages should show 1/1 or 2/2 tasks instead of 200/200.

Look at your output directory:

ls data/processed/orders/Before, you'd see hundreds of tiny parquet files with names like part-00001.parquet, part-00002.parquet, and so on. Now you'll see one clean file.

Why This Matters at Scale

Wrong partitioning breaks pipelines at scale. With 75 million records, having too many partitions creates coordination overhead. Having too few means you can't parallelize. And if your data is unevenly distributed (some partitions with 1 million records, others with 10,000), you get stragglers, slow tasks that hold up the entire job while everyone else waits.

Get partitioning right and your pipeline uses less memory, produces cleaner files, performs better downstream, and scales without crashing.

We've cut our runtime in half by eliminating redundant work and fixing partitioning. Next up: caching. We're still recomputing DataFrames multiple times, and that's costing us time. Let's fix that.

Strategic Caching: Stop Recomputing the Same Data

Here's a question: how many times do we use clean_df in our pipeline?

Look at main.py:

clean_df = transform_orders(raw_df)

logger.info(f"Transformation complete: {clean_df.count()} clean records")

metrics_df = create_metrics(clean_df) # Using clean_df here

logger.info(f"Generated {metrics_df.count()} metric records")

load_to_parquet(clean_df, output_path) # Using clean_df again

load_to_parquet(metrics_df, metrics_path)We use clean_df three times: once for the count, once to create metrics, and once to write it. Here's the catch: Spark recomputes that entire transformation pipeline every single time.

Remember, transformations are lazy. When you write clean_df = transform_orders(raw_df), Spark doesn't actually clean the data. It just creates a plan: "When someone needs this data, here's how to build it." Every time you use clean_df, Spark goes back to the raw CSVs, reads them, applies all your transformations, and produces the result. Three uses = three complete executions.

That's wasteful.

The Solution: Cache It

Caching tells Spark: "I'm going to use this DataFrame multiple times. Compute it once, keep it in memory, and reuse it."

Update main.py to cache clean_df after transformation:

def main():

# ... existing code ...

try:

spark = create_spark_session()

logger.info("Spark session created")

# Extract

raw_df = extract_all_data(spark)

logger.info("Extracted raw data from all sources")

# Transform

clean_df = transform_orders(raw_df)

# Cache because we'll use this multiple times

clean_df.cache()

logger.info(f"Transformation complete: {clean_df.count()} clean records")

# Create aggregated metrics

metrics_df = create_metrics(clean_df)

logger.info(f"Generated {metrics_df.count()} metric records")

# Load

output_path = "data/processed/orders"

metrics_path = "data/processed/metrics"

load_to_parquet(clean_df, output_path)

load_to_parquet(metrics_df, metrics_path)

# Clean up the cache when done

clean_df.unpersist()

runtime = (datetime.now() - start_time).total_seconds()

logger.info(f"Pipeline completed in {runtime:.2f} seconds")We added clean_df.cache() right after transformation and clean_df.unpersist() when we're done with it.

What Actually Happens

When you call .cache(), nothing happens immediately. Spark just marks that DataFrame as "cacheable." The first time you actually use it (the count operation), Spark computes the result and stores it in memory. Every subsequent use pulls from memory instead of recomputing.

The .unpersist() at the end frees up that memory. Not strictly necessary (Spark will eventually evict cached data when it needs space), but it's good practice to be explicit.

When to Cache (and When Not To)

Not every DataFrame needs caching. Use these guidelines:

Cache when:

- You use a DataFrame 2+ times

- The DataFrame is expensive to compute

- It's reasonably sized (Spark will spill to disk if it doesn't fit in memory, but excessive spilling hurts performance)

Don't cache when:

- You only use it once (wastes memory for no benefit)

- Computing it is cheaper than the cache overhead (very simple operations)

- You're caching so much data that Spark is constantly evicting and re-caching (check the Storage tab in Spark UI to see if this is happening)

For our pipeline, caching clean_df makes sense because we use it three times and it's small. Caching the raw data wouldn't help because we only transform it once.

Test the Changes

Run the pipeline:

python main.pyCheck the timing:

Pipeline completed in 18.11 secondsWe saved about 3 seconds with caching. Want to see what actually got cached? Check the Storage tab in the Spark UI to see how much data is in memory versus what has been spilled to disk. For our small dataset, everything should be in memory.

From 47 seconds at baseline to 18 seconds now — that's a 62% improvement from three optimizations: removing redundant counts, fixing partitioning, and caching strategically.

The performance gain from caching is smaller than partitioning because our dataset is tiny. With larger data, caching makes a much bigger difference.

Too Much Caching

Caching isn't free. It uses memory, and if you cache too much, Spark starts evicting data to make room for new caches. This causes thrashing, constant cache evictions and recomputations, which makes everything slower.

Cache strategically. If you'll use it more than once, cache it. If not, don't.

We've now eliminated redundant operations, fixed partitioning, and added strategic caching. Next up: filtering early. We're still cleaning all the data before removing test records, which is backwards. Let's fix that.

Filter Early: Don't Clean Data You'll Throw Away

Look at our transformation pipeline in transform_orders:

def transform_orders(df):

"""Apply all transformations in sequence"""

logger.info("Starting data transformation...")

df = clean_customer_id(df)

df = clean_price_column(df)

df = standardize_dates(df)

df = remove_test_data(df) # ← This should be first!

df = handle_duplicates(df)See the problem? We're cleaning customer IDs, parsing prices, and standardizing dates for all the records. Then, at the end, we remove test data and duplicates. We just wasted time cleaning data we're about to throw away.

It's like washing dirty dishes before checking which ones are broken. Why scrub something you're going to toss?

Why This Matters

Test data removal and deduplication are cheap operations because they're just filters. Price cleaning and date parsing are expensive because they involve regex operations and type conversions on every row.

Right now we're doing expensive work on 85 records, then filtering down to 75. We should filter to 75 first, then do expensive work on just those records.

With our tiny dataset, this won't save much time. But imagine production: you load 10 million records, 5% are test data and duplicates. That's 500,000 records you're cleaning for no reason. Early filtering means you only clean 9.5 million records instead of 10 million. That's real time saved.

The Fix: Reorder Transformations

Move the filters to the front. Change transform_orders to:

def transform_orders(df):

"""Apply all transformations in sequence"""

logger.info("Starting data transformation...")

# Filter first - remove data we won't use

df = remove_test_data(df)

df = handle_duplicates(df)

# Then do expensive transformations on clean data only

df = clean_customer_id(df)

df = clean_price_column(df)

df = standardize_dates(df)

# Cast quantity and add calculated fields

df = df.withColumn(

"quantity",

when(col("quantity").isNotNull(), col("quantity").cast(IntegerType()))

.otherwise(1)

)

df = df.withColumn("total_amount", col("unit_price") * col("quantity")) \

.withColumn("processing_date", current_date()) \

.withColumn("year", year(col("order_date"))) \

.withColumn("month", month(col("order_date")))

logger.info("Transformation complete")

return dfThe Principle: Push Down Filters

This is called predicate pushdown in database terminology, but the concept is simple: do your filtering as early as possible in the pipeline. Reduce your data size before doing expensive operations.

This applies beyond just test data:

- If you're only analyzing orders from 2024, filter by date right after reading

- If you only care about specific regions, filter by region immediately

- If you're joining two datasets and one is huge, filter both before joining

The general pattern: filter early, transform less.

Test the Changes

Run the pipeline:

python main.pyCheck the timing:

Pipeline completed in 17.71 secondsWe saved about a second. In production with millions of records, early filtering can be the difference between a 10-minute job and a 2-minute job.

When Order Matters

Not all transformations can be reordered. Some have dependencies:

- You can't calculate

total_amountbefore you've cleanedunit_price - You can't extract the year from

order_datebefore standardizing the date format - You can't deduplicate before you've standardized customer IDs (or you might miss duplicates)

But filters that don't depend on transformations? Move those to the front.

Let's tackle one final improvement: making the summary report efficient.

Efficient Aggregations: Compute Everything in One Pass

Remember that summary report we commented out earlier? Let's bring it back and fix it properly.

Here's what create_summary_report currently does:

def create_summary_report(df):

"""Generate summary statistics"""

logger.info("Generating summary report...")

total_orders = df.count()

unique_customers = df.select("customer_id").distinct().count()

unique_products = df.select("product_name").distinct().count()

total_revenue = df.agg(sum("total_amount")).collect()[0][0]

date_stats = df.agg(

min("order_date").alias("earliest"),

max("order_date").alias("latest")

).collect()[0]

region_count = df.groupBy("region").count().count()

# ... log everything ...Count how many times we scan the data. Six separate operations: count the orders, count distinct customers, count distinct products, sum revenue, get date range, and count regions. Each one reads through the entire DataFrame independently.

The Fix: Single Aggregation Pass

Spark lets you compute multiple aggregations in one pass. Here's how:

Replace create_summary_report with this optimized version:

def create_summary_report(df):

"""Generate summary statistics efficiently"""

logger.info("Generating summary report...")

# Compute everything in a single aggregation

stats = df.agg(

count("*").alias("total_orders"),

countDistinct("customer_id").alias("unique_customers"),

countDistinct("product_name").alias("unique_products"),

sum("total_amount").alias("total_revenue"),

min("order_date").alias("earliest_date"),

max("order_date").alias("latest_date"),

countDistinct("region").alias("regions")

).collect()[0]

summary = {

"total_orders": stats["total_orders"],

"unique_customers": stats["unique_customers"],

"unique_products": stats["unique_products"],

"total_revenue": stats["total_revenue"],

"date_range": f"{stats['earliest_date']} to {stats['latest_date']}",

"regions": stats["regions"]

}

logger.info("\n=== ETL Summary Report ===")

for key, value in summary.items():

logger.info(f"{key}: {value}")

logger.info("========================\n")

return summaryOne .agg() call, seven metrics computed. Spark scans the data once and calculates everything simultaneously.

Now uncomment the summary report call in main.py:

load_to_parquet(clean_df, output_path)

load_to_parquet(metrics_df, metrics_path)

# Generate summary report

summary = create_summary_report(clean_df)

# Clean up the cache when done

clean_df.unpersist()How This Works

When you chain multiple aggregations in .agg(), Spark sees them all at once and creates a single execution plan. Everything gets calculated together in one pass through the data, not sequentially.

This is the difference between:

- Six passes: Read → count → Read → distinct customers → Read → distinct products...

- One pass: Read → count + distinct customers + distinct products + sum + min + max + regions

Same results, fraction of the work.

Test the Final Pipeline

Run it:

python main.pyCheck the output:

=== ETL Summary Report ===

2025-11-07 23:14:22,285 - INFO - total_orders: 75

2025-11-07 23:14:22,285 - INFO - unique_customers: 53

2025-11-07 23:14:22,285 - INFO - unique_products: 74

2025-11-07 23:14:22,285 - INFO - total_revenue: 667.8700000000003

2025-11-07 23:14:22,285 - INFO - date_range: 2024-10-15 to 2024-11-10

2025-11-07 23:14:22,285 - INFO - regions: 4

2025-11-07 23:14:22,286 - INFO - ========================

2025-11-07 23:14:22,297 - INFO - Pipeline completed in 18.28 secondsWe're at 18 seconds. Adding the efficient summary back added less than a second because it computes everything in one pass. The old version with six separate scans would probably take 24+ seconds.

Before and After: The Complete Picture

Let's recap what we've done:

Baseline (47 seconds):

- Multiple counts scattered everywhere

- 200 partitions for 75 records

- No caching, constant recomputation

- Test data removed after expensive transformations

- Summary report with six separate scans

Optimized (18 seconds):

- Strategic counting only where needed

- 1 partition per output file

- Cached frequently-used DataFrames

- Filters first, transformations second

- Summary report in a single aggregation

Result: 61% faster with the same hardware, same data, just better code.

And here's the thing: these optimizations scale. With 75,000 records instead of 75, the improvements would be even more dramatic. With 75 million records, proper optimization is the difference between a job that completes and one that crashes.

You've now seen the core optimization techniques that solve most real-world performance problems. Let's wrap up with what you've learned and when to apply these patterns.

What You've Accomplished

You can diagnose performance problems. The Spark UI showed you exactly where time was being spent. Too many jobs meant redundant operations. Too many tasks meant partitioning problems. Now you know how to read those signals.

You know when and how to optimize. Remove unnecessary work first. Fix obvious problems, such as incorrect partition counts. Cache strategically when data gets reused. Filter early to reduce data volume. Combine aggregations into single passes. Each technique targets a specific bottleneck.

You understand the tradeoffs. Caching uses memory. Coalescing reduces parallelism. Different situations need different techniques. Pick the right ones for your problem.

You learned the process: measure, identify bottlenecks, fix them, measure again. That process works whether you're optimizing a 75-record tutorial or a production pipeline processing terabytes.

When to Apply These Techniques

Don't optimize prematurely. If your pipeline runs in 30 seconds and runs once a day, it's fine. Spend your time building features instead of shaving seconds.

Optimize when:

- Your pipeline can't finish before the next run starts

- You're hitting memory limits or crashes

- Jobs are taking hours when they should take minutes

- You're paying significant cloud costs for compute time

Then follow the process you just learned: measure what's slow, fix the biggest bottleneck, measure again. Repeat until it's fast enough.

What's Next

You've optimized a single-machine pipeline. The next tutorial covers integrating PySpark with the broader big data ecosystem: connecting to data warehouses, working with cloud storage, orchestrating with Airflow, and understanding when to scale to a real cluster.

Before you move on to distributed clusters and ecosystem integration, take what you've learned and apply it. Find a slow Spark job - at work, in a project, or just a dataset you're curious about. Profile it with the Spark UI. Apply these optimizations. See the improvement for yourself.

In production, enable AQE (spark.sql.adaptive.enabled = true) and let Spark's automatic optimizations work alongside your manual tuning.

One Last Thing

Performance optimization feels intimidating when you're starting out. It seems like it requires deep expertise in Spark internals, JVM tuning, and cluster configuration.

But as you just saw, most performance problems come from a handful of common mistakes. Unnecessary operations. Wrong partitioning. Missing caches. Poor filtering strategies. Fix those, and you've solved 80% of real-world performance issues.

You don't need to be a Spark expert to write fast code. You need to understand what Spark is doing, identify the waste, and eliminate it. That's exactly what you did today.

Now go make something fast.